Growing up in Singapore, I have often heard the older generation speak longingly of the "kampung spirit" — a sense of neighbourliness and mutual care rooted in the country’s village past. This spirit was something I had never truly experienced. Singapore’s public housing was built upon this same ideal for her communities. In the early years, the long corridors of the Housing and Development Board (HDB) flats were designed to bring people closer.

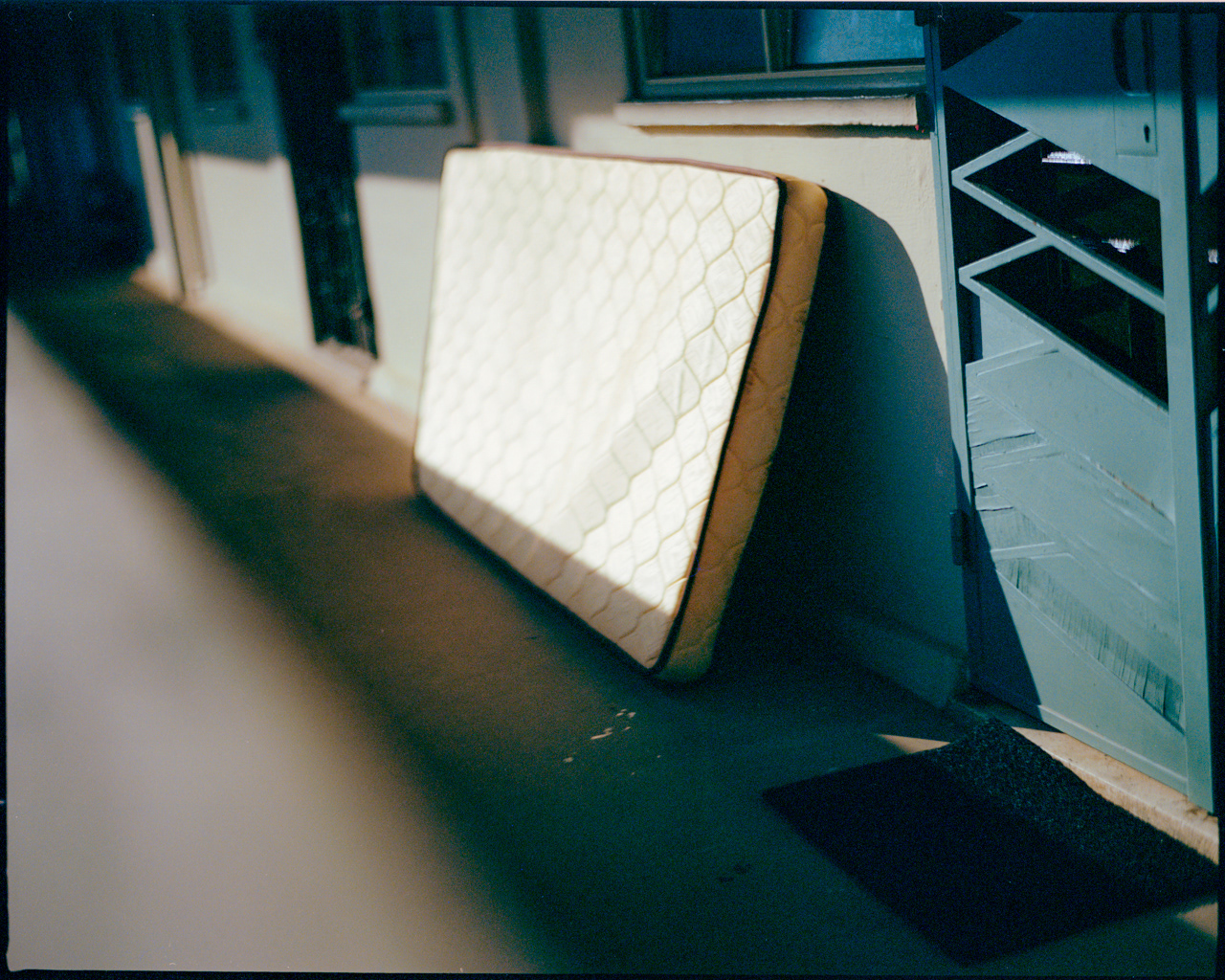

When I encountered Block 34 Whampoa West, a flat which boasted Singapore's longest curved corridor stretching 320 metres and lined with 46 homes on each level, I wondered if that spirit still lingered within its bend. Standing along the curve, I could see how the architecture bore the traces of time. Many empty units held a silence that felt surreal.

As I spent time there, I thought about Singapore’s ageing population — encouraged to live independently, yet often surrounded by a quiet kind of isolation. Beneath that stillness, I found persistence: the small, deliberate acts that held life together even when connections felt remote.

I worked with natural light and film to evoke a sense of nostalgia, mirroring the slow, contemplative rhythm of daily life in the block. I lingered from early morning to late afternoon, through weekdays and weekends, until the corridor itself seemed to breathe.

Over time, I met residents who had taken it upon themselves to reach out to their neighbours — gestures as simple as a greeting, exchanging festive treats, or gifting a plant. These moments reminded me that while architecture shapes how we live, it is the smallest human gestures that sustain community.

Though rooted in Singapore, the questions are universal: How do we live together in increasingly urbanised worlds? What remains of community when the spaces built for connection begin to empty? Through the gentle curve of one corridor, I seek to reflect a broader human condition — one that holds the tension between solitude and belonging.